An extremely busy couple of days in Phnom Penh, not helped by the fact that I had my passport stolen while recording some stuff at the water festival on the weekend.

All manner of bureaucratic problems await me before I get out of Cambodia, but I'm pressing ahead with the assignment and am now in Battembang, a four hour drive from the capital.

I'm heading out into the wilds near the Thai border shortly, so this is just a quick update before I disappear for a couple of days.

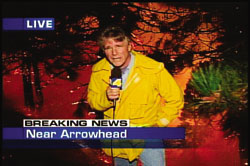

I've written my first piece for BBC News Online...here's a sneaky peak and a couple of pictures taken by Sean Sutton from MAG, who I'm travelling with.

I'll probably be back from the sticks on Thursday. More then.

Chum Sakhorn has no doubts about who was to blame for robbing him of both of his legs.

On one of his two artificial limbs, Sakhorn – a 38 year old father of 7 – has written the words “I was cheated by war” in blue marker pen.

In 1987, Chum Sakhorn was fighting the infamous Khmer Rouge in one of its strongholds near the border between Cambodia and Thailand when he stepped on a landmine.

“I was fighting in Phnom Malay,” he told me.

“I was transporting equipment for my regiment. I wanted to cross a bridge – but it had been blown up by a big anti-tank mine.

“I couldn’t go across, so I took a detour. I spotted one mine and disarmed it but while I was walking along a small path I stepped on another one.”

The resulting explosion blew off both of Chum Sakhorn’s legs below the knees.

He is now among Cambodia’s estimated 40,000 chon pika – or amputees. With a population of around 11.5 million, Cambodia has one amputee for every 290 people – one of the highest ratios in the world.

But Chum Sakhorn says the landmine he stepped on also blew away any chance he had of a successful future.

16 years on from his accident, he ekes out a living selling books and postcards to tourists in Phnom Penh’s central market with a group of other mine-injured former soldiers. A local bookseller lends them the merchandise and pays them a small commission on each item sold.

Most retailers in the market, though, are less sympathetic. They regard the amputees as the lowest of the low.

“Life for amputees in Cambodia is very bad,” Sakhorn says.

“The shopkeepers don’t even like me standing in front of their stores.

“Sometimes the police try to arrest us, or confiscate our merchandise. We’re treated like outcasts – the authorities harrass us because they think we’re below them.”

Outside the main cities, 85% of Cambodians rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. Cambodia’s chronic mine contamination problem means the threat of death or serious injury is a daily reality for most people here.

“A recent survey found that more than 40% of the villages in Cambodia have a mine problem,” says Sean Sutton from the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), an international mine clearance charity.

“Cambodia was constantly at war from more than 20 years. Landmines were widely used by all sides.

“Each time an area changed hands fresh mines were laid in areas that were already heavily contamined.”

Indeed, Pol Pot – the head of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime responsible for the deaths of millions of Cambodians during the 1970s – described landmines as his “perfect soldiers,” so effective were they at causing fear and death.

Democratic elections in 1993 heralded the start of a period of relative calm in Cambodia and many displaced people began returning home from refugee camps in Thailand.

Yet this population movement brought another wave of landmine casualties.

“Many villagers lost limbs trying to reclaim the land they’d been forced from years before,” explains Sean Sutton.

“Many of them knew their villages and fields were mined but they needed to work the land in order to survive.

“They knew they were risking their lives – but they had no choice.”

Picture: Chum Sakhorn at work

Picture: Amputees ekeing out a living -- Phnom Penh Central Market

Picture: Comparing Legs